Welcome to the 2024 presidential election season.

Your options this year include one Democrat and one Republican, neither of whom probably represent the full extent on how you feel about the world.

You could vote for a third party or an independent, but neither have won the election in the past 150 years. Plus, you risk letting in a candidate you really don’t like.

You will play this same game again in four years—same teams, sometimes new players.

But what if we could see more minor league teams playing in the great game of United States’ elections?

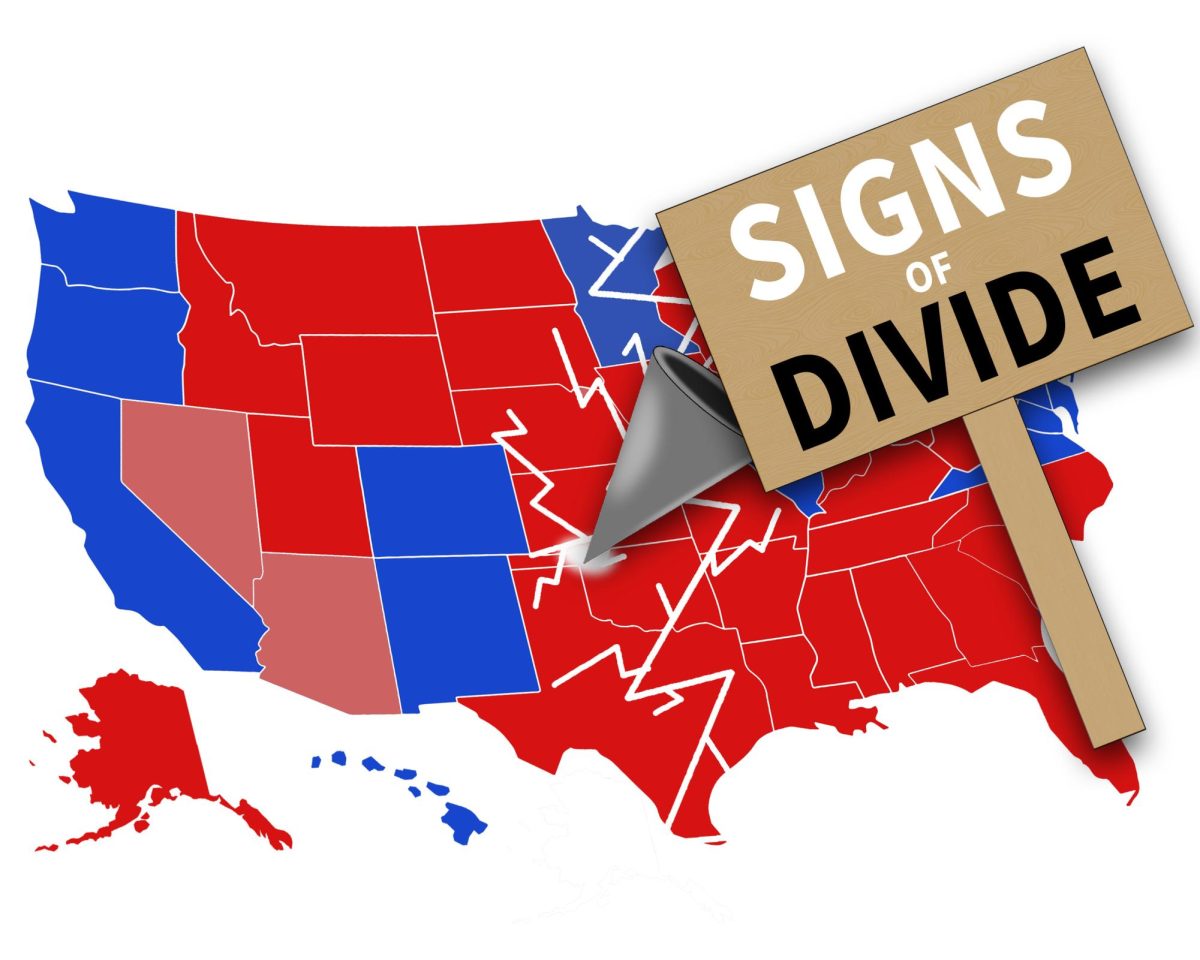

Under the U.S.’s first-past-the-post voting system (FPTP), voters are never fully represented by the choices they have.

Ranked choice voting is an effective alternative that allows voters to be better heard.

While ranked choice voting comes in many, many forms, this argument centers around single transferable vote (STV) and instant-runoff voting (IRV).

In both of these forms, ranked choice voting works by voters ranking their top candidates rather than just picking one.

Under STV, when a candidate fails to meet a vote number threshold, that vote transfers to whoever a voter places as second then third and onward until someone is selected.

Under IRV, each ranking—first, second or third—is worth a different number of points, and the candidate with the most points wins.

With FPTP, the U.S.’s voting system where each voter gets one vote and winner takes all, there are many problems, but the most prominent. One problem in question is the harsh two-party split, called Duverger’s Law in some cases.

The law is simple: single constituency, plurality-wins systems will break into two parties. Single constituency means one person is elected per spot, and plurality wins means that whoever gets the most votes overall is the winner.

There are some major issues related to having only two viable parties for the presidency, among other positions, one of which being the lesser of two evils principle.

It means what it says. In situations without a clear answer, people will most often choose what they pick to be the lesser evil in the situation.

According to the Washington Post, in 2016 both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were sitting under a 60% approval rating. And despite this, these were the candidates that received the most votes.

Clinton won the popular vote this year, and Trump won the Electoral College, putting him in office.

With historically only two candidates being viable for the presidency, representing the wide range of how voters feel is impossible.

The Republican and Democrat parties must stand on broad enough platforms to attract the most votes. But the broadest opinions don’t encapsulate how many voters really feel.

But why then do these two parties garner the most votes? Let’s introduce the spoiler effect.

According to Merriam Webster, a spoiler is a candidate with little or no chance of winning but capable of depriving a rival of success.

In the United States, third parties act as spoiler votes. Often issue based, third parties tend to serve specific purpose based around one central topic. The Green Party is based on stronger climate change measures, and the Libertarian Party wants to limit the power of the government, to name a few.

Essentially, voting for a third party acts to take away a vote for the party, Democrat or Republican, that has the highest chance of winning.

For the Green Party, it is a spoiler for the Democratic Party. For the Libertarian Party, it is a spoiler for the Republican Party.

The most well-known example of a spoiler vote having a great effect was in the 2000 election of Al Gore and George W. Bush.

Considered one of the closest elections to date, this election was the fourth of five where the popular vote failed to select the winning candidate.

On election night of this year, the vote for Florida had yet to be called. It ended up being around a 500-vote difference, an abysmally small difference in a state where almost 6 million voted.

With such a small difference, Ralph Nader of the Green Party was a spoiler in this case, garnering 97,000 votes in Florida this year. No Republican spoiler party had acquired near as much, even combining all of them.

These things can be fixed.

Under RCV, the spoiler effect is significantly lessened, according to a study from Springer.

With this system, there is no fear of a vote being wasted. Voters can rank candidates sincerely without potentially contributing to a less popular candidate getting into office.

Voting for the Green Party won’t lose Gore the vote; voting for the Libertarian Party won’t lose a state for Bush.

One common argument against using RCV is that it is too confusing for voters and can lead to ballots being thrown out.

At its base level, ranking favorite candidates is not intrinsically difficult. If anything, RCV can inspire voters to learn more about the candidates they vote for by allowing more than one vote.

Confusion is created most of the time by poor communication rather than a fault of RCV itself. RCV is just as difficult as FPTP, just with a different set of instructions.

RCV is currently used in Alaska, in cities across California, in Maine and more.

The argument made about ballots being thrown out lacks context. In a FPTP election, just about half the votes are “thrown out” or no longer matter when a candidate loses.

For those voting in ranked choice that did not add multiple rankings and instead just picked one, that is essentially just a FPTP vote.

If a voter only picked one when a candidate loses, the votes are gone. That works the same as how current elections would work.

Another argument commonly thrown around when RCV is brought up is that the votes take too long to tally.

This is only an issue because it has been made one. Counting votes as a process should be given more time to accurately tally votes anyway, even if it means not receiving news the night of.

By allowing more time to count votes, the margin of error surely decreases. After all, rushed work can be prone to flaws.

Overall, there is no perfect voting system. Every one of them bears some sort of problem too grand to solve.

But if we’re choosing between temporary confusion and loss of choice, the answer is clear.

Under ranked choice voting, there’s a new world of choices opened up to American voters.

The Editorial Staff can be reached at 581-2812 or at deneic@gmail.com.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)