Throughout all of time and across all cultures, clothing has held significant meaning.

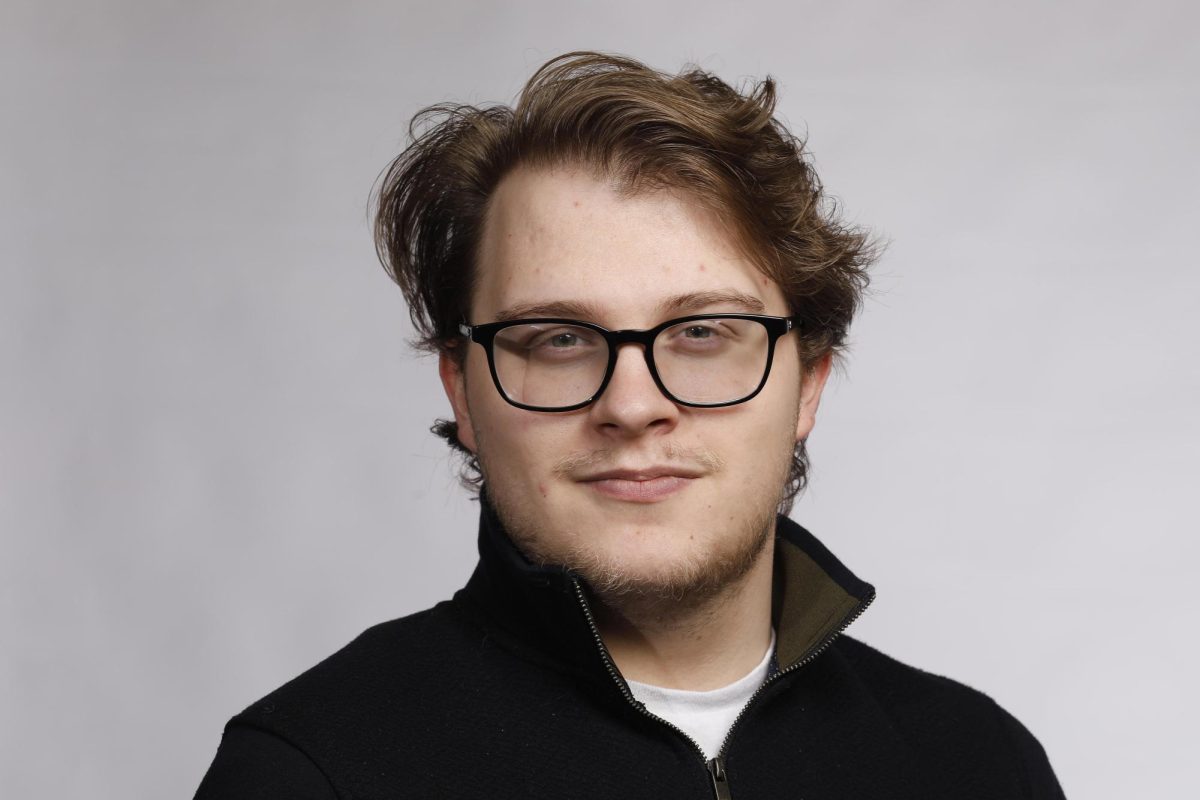

That sentiment rings true for Samira Dadson, a studio art graduate student studying fashion at EIU.

Across the world, women are harassed for the clothes they wear. In the U.S., almost nine out of 10 women experience street harassment before the age of 17, research from ILR and Hollaback found. Women must put up with catcalling, assault and more, questioning which is more important: self-expression or safety?

Here at EIU, Dadson is taking matters into her own hands, making statement pieces meant to end that question rather than answer it.

In Ghana, Dadson’s home country, what clothes someone wears makes all the difference in how they are perceived. Depending on the color and pattern, clothing in Ghana can communicate joy, grief and much more.

Modesty in Ghana

With that, modesty is the standard in Ghana. Dadson has been shamed for the way she looked since she was a kid — an experience shared by many Ghanaian women, she said.

When Dadson was in middle school, her class was taught about sexual assault and urged to dress modestly to avoid being targeted. Dadson disagreed with the message of modesty and spoke out against her instructor.

“I was basically just saying that someway, somehow the blame always falls on the woman,” Dadson said.

Her whole class erupted with something to say, insulting Dadson’s body and appearance.

But Dadson wasn’t wearing anything out of the ordinary. She had on a long skirt and normal-length top. It was her body shape, she said, that sparked the outcry.

“I had classmates who were dressed crazier than I was, but because they didn’t have the curves at that age, they used to get away with it,” she said.

The Ghanaian Statistical Service reported in 2016 that 65% of women in Ghana would blame the victim if they were wearing revealing clothing in a rape scenario, 10% higher than the number of men.

Dadson said this shaming was an experience shared by most if not all Ghanaian women.

But ever since she was little, Dadson has loved clothing.

The Modesty Garment Set

Dadson came to the EIU graduate program this year with one goal in mind: to make powerful art using clothing.

In her first clothing set at EIU, Dadson created three pieces of clothing ranging from modest to immodest, directly inspired by the experiences of women in Ghana. The set was titled “Kae,” which means remember in Asante Twi, a local Ghanaian language.

“I named it that to remind people that at the heart of every nonconformist Ghanaian youth is a Ghanaian identity,” Dadson said. “So, treating each and every one with love and respect is a must.”

The most modest piece was covered head to toe with a skirt going to the floor and long sleeves. Alongside that, Dadson made a traditional African headpiece to be worn with the dress.

Model Aryanna Tunstall wore the modest piece in the trio of garments. She said her role in the artwork was to be inconspicuous and closed into herself, hiding from the male gaze.

“Even though I was in clothing I would never pick for myself, I still felt pretty,” she said.

For the garment representing immodesty, Dadson wrote insults she and other women around her have heard on denim fabric– denim being closely intertwined with rebellion– and sewed those patches into the crop top and ripped pants.

Additionally, she used traditional Ghanaian patterns and fabric called batik in the clothing to represent themes like wealth and power.

From Marketing to Making Clothes

But Dadson didn’t start making clothing until recently; it took a long time to get here.

She made her first garment only ten years ago when she was still in college in Ghana studying marketing.

“They don’t encourage people to pursue arts where I’m from,” she said.

The first ever garment she made was a peplum top.

“I was very excited after making that,” she said. “Then I moved on to making dresses and skirts.”

After graduating, Dadson worked in the publicity department at a bank in Ghana while sewing on the side. She knew that marketing wasn’t the path for her, but she felt pressured to stay.

In 2020, though, Dadson took a huge leap: going back to school for fashion.

While working full time, Dadson started taking fashion classes from 6 to 9 p.m., doing homework late into the night after.

“I was always tired,” she said. “I was always sleepy. But somehow, I managed to pull through.”

In 2022, Samira fully committed to fashion. She left her job and attended Riohs College of Design in Ghana. There, she said she learned how to make intricate, functional clothing.

But she wanted to do more. She wanted to make art that would transcend the folds of her skirts and shirts.

A Swing and a Miss?

In talking with a friend in fashion from the U.S., Dadson decided she needed to leave Ghana and just come to the U.S. where she could get a fresh, new perspective on clothing as an art form.

Dadson considered her modesty set a success, saying she was proud of the outcome. However, being in the U.S., her message did not land quite how she had hoped.

Because of the differences in culture, some of the styles she made were not perceived as risky.

“But that’s the point,” Dadson said. “It’s not even that short, but the person who wears it faces that kind of discrimination.”

Unlike Dadson’s experiences, Tunstall said she has never been directly harassed for how she dresses.

“You get the catcalls; you get the comments,” Tunstall said. “I never really let that bother me.”

Tunstall said she could relate to Dadson’s theme but not directly.

Self-describing her clothing style as eccentric, fellow studio art grad student Olivia Stout said she is known for her bright-colored, unique outfits.

But being in the U.S., Stout said she hasn’t had any problems aside from some unkind glances and scoffs.

“But every woman gets catcalled,” she said.

The Next Step: Clothing Waste

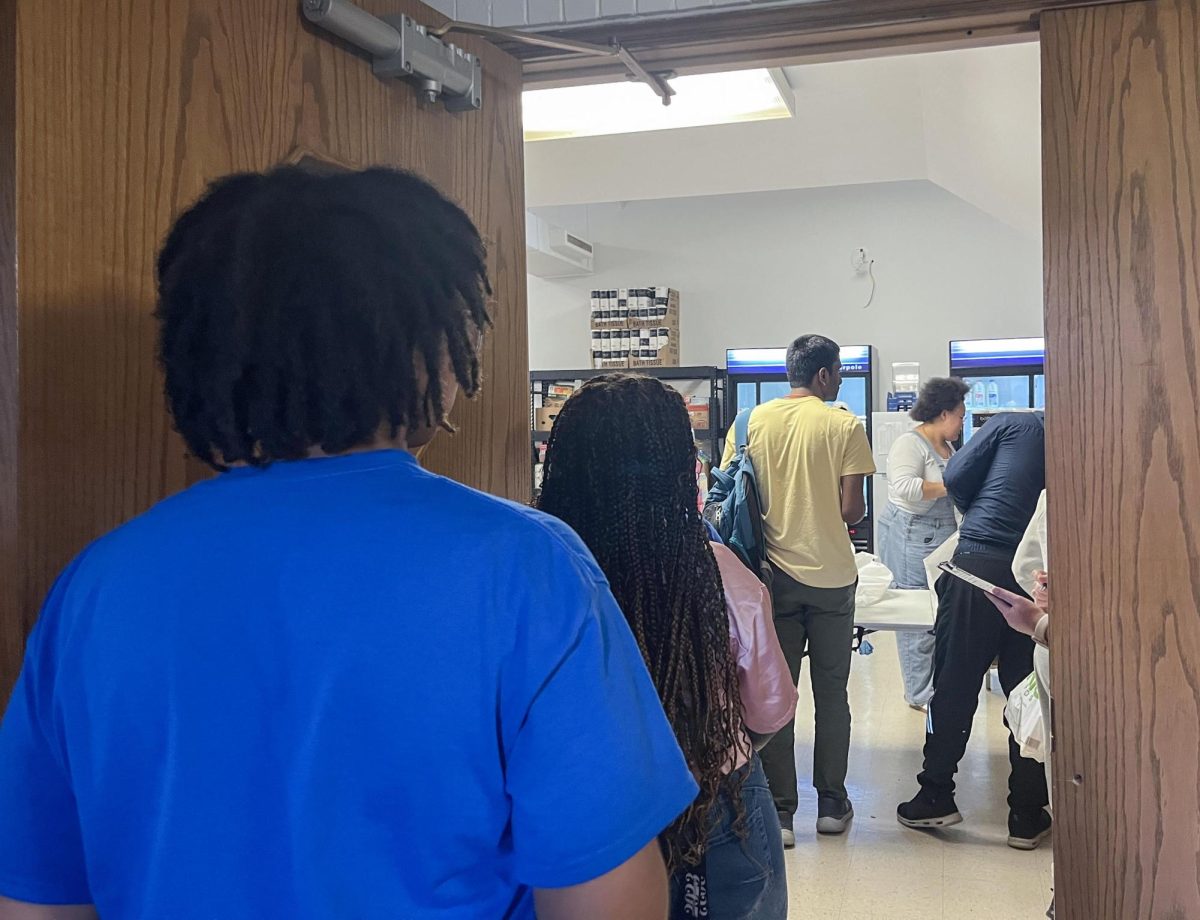

That difference in culture inspired Dadson to step into a new realm: U.S. clothing waste.

According to Dadson, the global north, including the U.S. and Europe, sends millions of pounds of clothing to Ghana every week. She said that when donating clothing to companies like Goodwill, much of the clothing is sent straight to landfills and end up polluting her home.

In response, Dadson created her most recent work of art. The symbolic piece titled “Dead White Man’s Clothes” features a connected dress and blanket made out of donated clothes.

From there, Dadson crystallized the clothing to better hold its shape, creating a wearable work of art to bring awareness to fast fashion.

She has started slowly rolling out her messages to larger audiences. She said she believes these things have to start small.

“She doesn’t make clothes just to make them,” Tunstall said. “She really believes and wants to spread the messages she's trying to convey in her garments.”

Advocacy in the Future

Currently, within her advocacy, Dadson is looking to work with both the Or Foundation and the Safe Space Foundation, two prominent advocacy groups in Ghana.

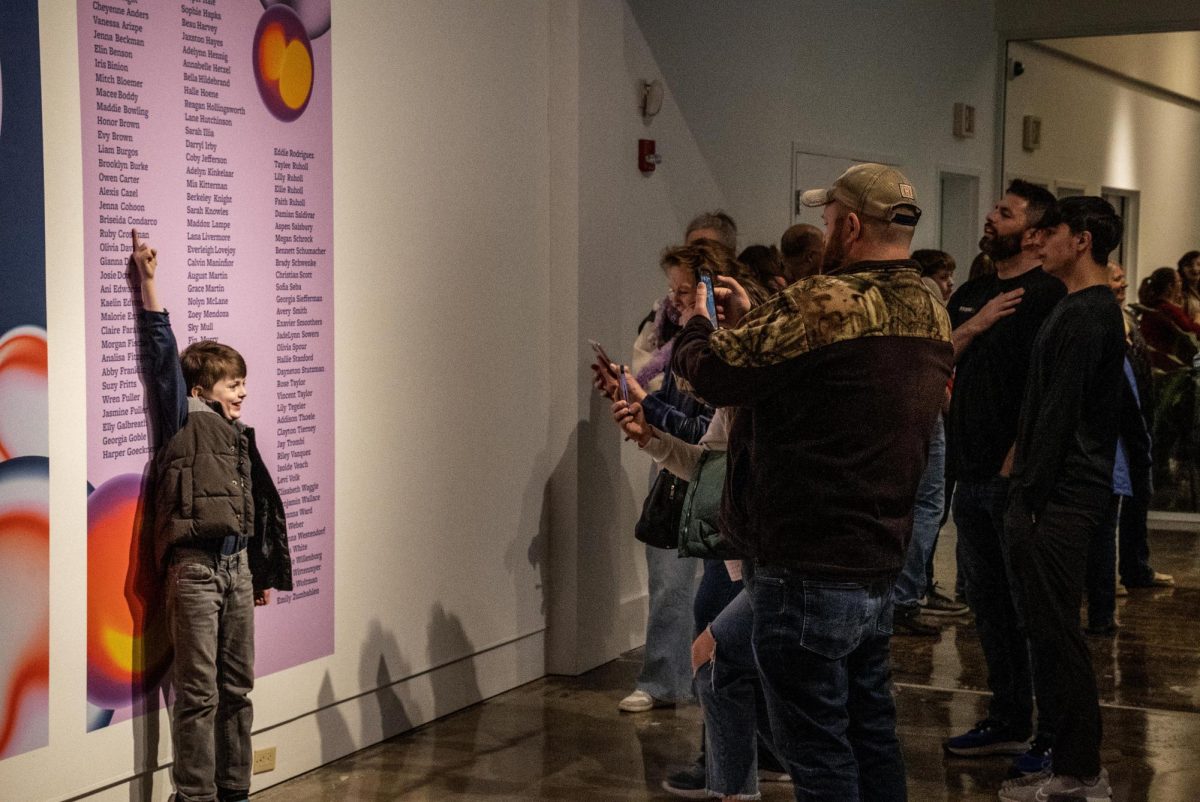

Her waste colonization piece is on view in the Tarble Arts Center until 5 p.m. May 3 as part of the graduate art exhibition being held there.

Above all else, Dadson said she was proud of herself for what she’s done, both as an artist and advocate.

“I think I always knew that I would end up in a place where I was doing art, but I didn't know how I was going to end up in that place,” she said. “But the old me would be very happy.”

Alli Hausman can be reached at 581-2812 or at athausman@eiu.edu.

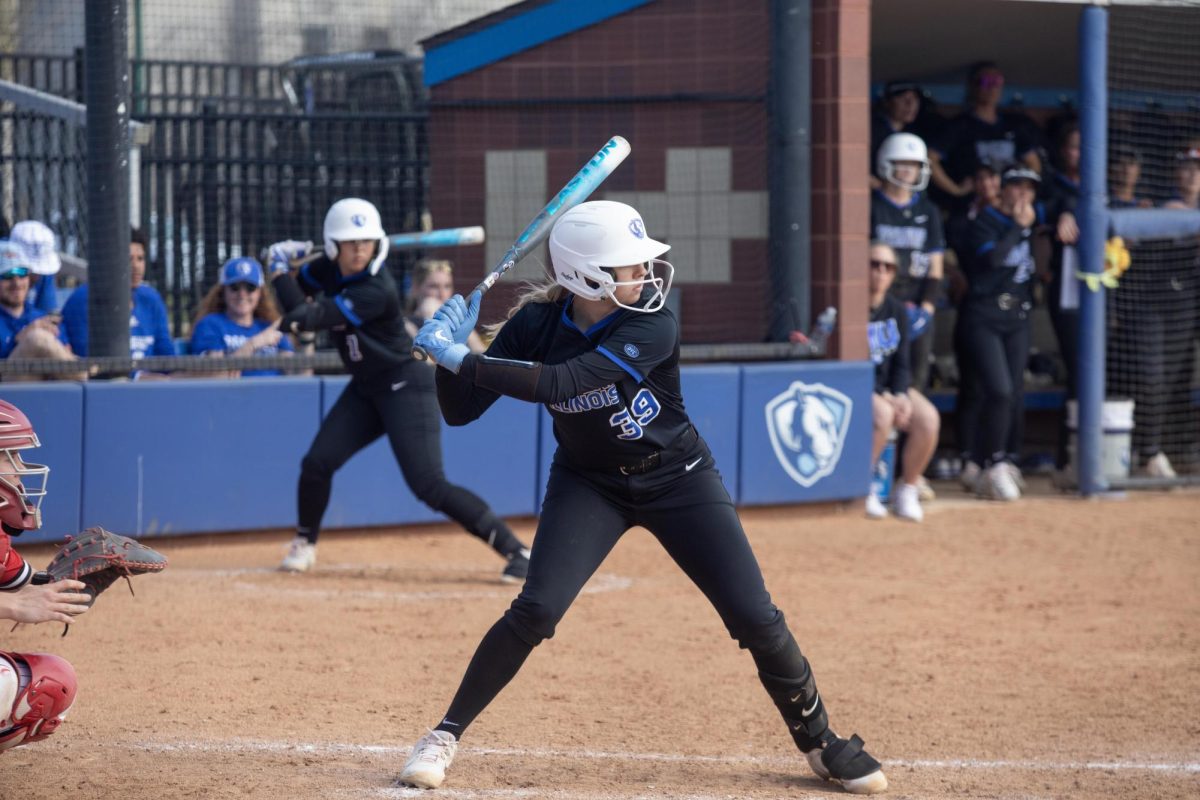

![[Thumbnail Edition] Eastern Illinois softball senior infielder Briana Gonzalez resetting in the batter's box after a pitch at Williams Field during Eastern’s first game against Southeast Missouri State as Eastern split the games as Eastern lost the first game 3-0 and won the second 8-5 on March 28.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/SBSEMO_11_O-1-e1743993806746-1200x692.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Junior right-handed Pitcher Lukas Touma catches at the game against Bradley University Tuesday](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MBSN_14_O-e1743293284377-1200x670.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)

![The Weeklings lead guitarist John Merjave [Left] and guitarist Bob Burger [Right] perform "I Am the Walrus" at The Weeklings Beatles Bash concert in the Dvorak Concert Hall on Saturday.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WL_01_O-1200x900.jpg)

![The team listens as its captain Patience Cox [Number 25] lectures to them about what's appropriate to talk about through practice during "The Wolves" on Thursday, March 6, in the Black Box Theatre in the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WolvesPre-12-1200x800.jpg)