As of last Tuesday, spring has officially begun. But the warm temperatures have been around for quite some time.

Think back to February.

Birds were singing a shrill chorus. Squirrels were running amok across the sidewalks. Students and community members alike were out in shorts and T-shirts.

Should one believe the prediction of Punxsutawney Phil, it would appear spring had arrived back then with temperatures being in the upper 50s across much of the month.

But it wasn’t spring then. At least not yet.

Through the month of February, Illinois and much of the Midwest experienced a phenomenon known as false spring.

False springs are defined by climatologist Cameron Craig as periods of abnormal warmth in the winter season followed by a snap back to cold weather.

According to Craig, false springs are a biological occurrence rather than a climatological one, meaning there isn’t a specific temperature threshold that defines a false spring. Rather, false springs happen when plants and animals resume activity ahead of schedule just to be shut down by frost burn when the temperatures snap back to cold.

“People ask, ‘Is this unique?’” Craig said. “No, it’s not unique. This has happened throughout our data collection since 1895.”

So far this winter season, Charleston saw a high of 77 degrees on Feb. 26; the average for that day was 67.5 degrees.

In March of 1925, the Charleston area saw temperatures of 80 degrees, Craig said. In 1917, it hit 78 degrees—same in 1903.

The issue with false springs, EIU plant ecologist Scott Meiners said, is not the fact that it gets warm early but rather the extended warm temperatures.

From a plant’s perspective, Meiners said, temperature is the best way to determine where it is in the year.

When long periods of warmth arrive after some cold, many plants are signaled to resume activity and begin growing again, he said. In these early growth stages, the plants are sensitive and susceptible to the cold.

For Meiners last year, his pawpaw trees bloomed early. Though these native plants bloom in March normally, the pawpaws had leafed out by February.

When the cold snap came in mid to late March, the leaves and flowers of his pawpaws froze and dropped off, struggling to grow back the rest of the season.

“That’s really hard on plant populations to sustain that sort of thing,” Meiners said.

During false springs, non-native species often struggle more than their native counterparts, behavioral ecologist and founder of the Urban Butterfly Initiative Paul Switzer said.

For example, should an orchard tree, like an apple tree, begin to flower in a false spring, the following cold snap can nip the tree’s flowers, leaving the owner with no fruit that year, Meiners said.

Plants don’t just have to replace the leaves they lose; they must restart growth, using more nutrients, he said. Damaged plant tissues can also lead to pathogen susceptibility.

The rapid temperature switch is where the biggest problems arise, Meiners said.

In animals active during winter, like the fox squirrels seen across EIU’s campus, the warm temperatures associated with false spring prompt more activity, said Switzer.

“If you go out to Lake Charleston during one of our warm days, you may see male red-winged blackbirds singing along the levee, doing their best to stake out territories for the coming breeding season,” Switzer said.

Some insects may become more active, seeking mates and food during a false spring only to retreat back into hiding when the cold comes back, he said.

Hibernating animals, like groundhogs, will often stay in their burrows until consistent spring temperatures arrive, said Switzer.

According to Craig, one key component for making a false spring is changes in the jet stream—the west to east flowing currents of air that circle the globe.

One primary factor that changes the jet stream is arctic oscillation, shifting pressure from the atmosphere.

During a negative arctic oscillation, ridges of cold air and ridges of warm air combat one another, allowing the cold air to move further south from the Arctic.

During a positive arctic oscillation, the warm jet stream is stronger and traps in the cold air in northern regions.

Neutral phases occur when the arctic oscillation is not strong in either direction, positive or negative.

Typically, the oscillation changes quite rapidly, over two days on average, Craig said. When it gets stuck for days on end in neutral or positive modes, those are instances where false springs can occur.

This year, the arctic oscillation went positive around Feb. 18 and maintained that positive quality until around Feb. 28, when temperatures dropped to a low of 22 degrees. During this time, growth began in many plants, including Craigs’ magnolia tree and the magnolia tree outside of Buzzard Hall. This was a potential false spring event.

According to Craig, the most recent long false spring was in 2012— which would go on to become a drought year.

2012 had a majority neutral arctic oscillation, going positive often as well, with the cold air in the jet stream bottlenecked. In the neutral phases, the cold air couldn’t make it far enough south. It took Hurricane Isaac to break the stream and release the cold air again.

This drought caused extremely high temperatures in Charleston, breaking five records in March of that year, according to Craig.

So far this season, Charleston has been in a majority negative oscillation, said Craig. There have been back and forths between low temperatures—a low of negative 12 in January—and high temperatures—the 70-degree weather.

However, for Meiners, Switzer and Craig, the false spring event was not what concerned them about the current season. Rather, all three brought up a different fear: climate change.

“I’m not a huge fan of winter, so I kind of like warm spells because it helps me think spring is on its way, even if the cold reality of winter is likely to return before we truly hit spring,” Switzer said. “But the trend for warmer and warmer weather over long periods of time –climate change– worries me a great deal.”

False springs are not directly caused by climate change. However, the earlier start to spring that has been occurring in the past several years is, said Craig.

According to a Climate Central study, cold streaks have shrunk by six days on average across the U.S since 1970. The study found that Champaign had lost eight days of cold. Peoria tied for the third largest change in the studied locations, losing 14 days.

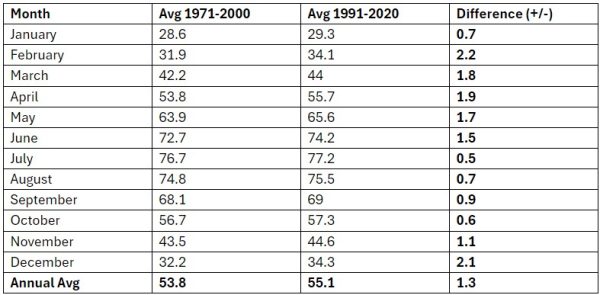

Looking at the climate normals—the 30-year averages—for Charleston from the National Weather Service station on campus, the warming is evident.

From the 1972-2000 average to the 1991-2020 average, temperatures increased across the board by 1.3 degrees.

The late winter and early spring months saw a greater increase compared to fall and summer months. In February specifically, there was 2.2-degree increase—the largest of any month.

These temperatures shifts are causing problems in both global and local ecosystems greater than anything a false spring can do, Switzer said.

“If spring is coming earlier and earlier year after year, insects and plants may be on different schedules depending on which cues they use to determine that spring is here,” Switzer said.

According to Meiners, one species this affects is the spring beauty, a white flower that carpets the bottom of forests.

Spring beauties are early blooming flowers that are pollinated primarily by andrenid bees. These bees are specialist miner bees, nesting underground. According to the Missouri Department of Conservation, this species’ “life cycle is timed to correspond precisely to the blooming of specific flowers.”

Over time, Meiners said, these bees and flowers are starting to fall out of sync with one another, alongside many other soil dwelling species.

The temperature changes are shifting when plants germinate and when many animals resume activity. Depending on whether species use soil or air temperature or even the amount of light present to resume activity, species are getting started at different times, Switzer said.

Many other bees, like honey bees, are seeing population declines from climate changes, a National Library of Medicine study found. Additionally, the study said that food supply and the price of food could be in danger should honey bee populations continue to fall. Currently, honey bees pollinate $15 billion worth of crops in the U.S., the USDA said.

With the lack of cold has come a lack of snow.

This winter season, Charleston received around four inches of snow, Craig said. According to Craig, the 30-year-average for snow in Charleston is 19 inches.

In 2022, Charleston received almost the same amount of snow as this year, hitting around four inches on the ground in late January. Just like this year, that snow did not stick around, melting within days.

Similarly in 2021, Charleston received several small bursts of snow, lasting for a maximum of three days in February. Charleston saw one day with six inches of snow in 2021, but it melted after only two days.

One effect of this lack of snow can be seen in pest insect populations.

Insects like June bugs and Asian lady beetles hibernate over the winter season. In order to kill these pest insects, according to Craig there must be at least 13 inches of frozen soil for at least a month or two.

“In order to get that much frozen, your whole season has to be below freezing,” Craig said.

Overall, insect populations are in decline, Biological Conservation reported. However, insects that benefit from the warmer temperatures are seeing increases.

Mosquitoes, who are active in warmer temperatures, are one such species. Last August was the hottest on record, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found. With warmer temperatures, Climate Central found that the number of hospitable days for mosquitoes has increased. This has allowed mosquitoes to be active for longer in the season.

With these aforementioned shifts, Craig also added that the weather and climate are getting more erratic.

Craig defined the climate as a “rollercoaster shooting up and down.”

The jumps in temperature are beginning to become more irregular, changing quickly from hot to cold back to hot, Craig said. These jumps affect plant and animal populations.

For example, recently Lake Charleston saw a die-off in the fish gizzard shad. The event was small, but it was caused by the cold spike in February.

Alongside these other changes, Craig noted that the jet streams appear to be becoming more erratic, making extreme weather more severe and more common.

Typically, there are two jets, the polar and subtropical jets—cold and warm. Breaks in these jets are appearing more than ever before, Craig said.

The Alfred Wegener Institute found these changes to be directly linked to climate change and the decline in Arctic sea ice.

Looking forward, Craig predicts that winter as we define it—snow and harsh cold—will disappear in the Midwest.

“100 years ago, you could definitely say, ‘We’re in spring,’” Craig said. “Nature will do what it wants, and we are exacerbating the situation with human activity.”

Alli Hausman can be reached at 581-2812 or athausman@eiu.edu.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)

![[Thumbnail] Eastern's Old Main was quiet Thursday morning while educators who had left the office to strike picketed outside.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Strike_01_LT_O-800x1200.jpg)