Rachel Pappas perseveres through Vocal Cord Dysfunction

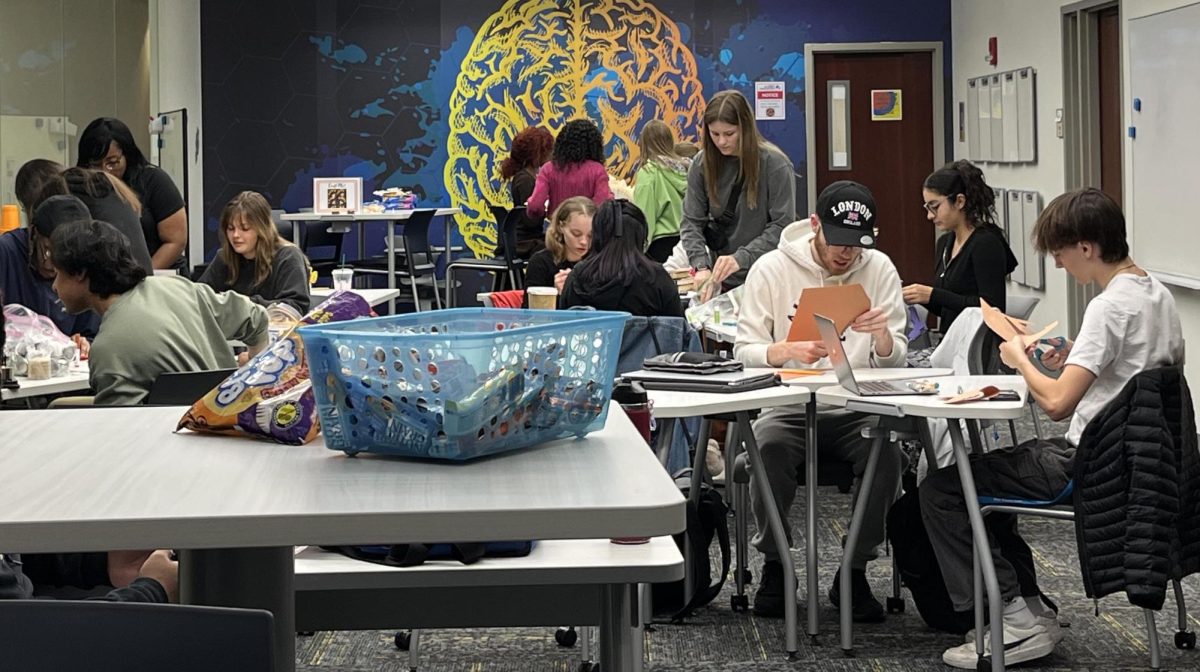

Karina Delgado | The Daily Eastern News Rachel Pappas boots the ball up the field as a defender runs up on her during Eastern’s 3-1 victory over Chicago State Sept. 15 at Lakeside Field. That match was the first time this season Pappas was able to play a whole 90 minutes.

September 26, 2019

Just breathe.

Go ahead, try it.

Easy, right?

Breathing is an involuntary action that we do not directly, consciously control; it happens naturally.

But when athletes are told to breathe, it usually is because they are running a lot and coaches tell them to breathe to help them recover from the exertion of so much energy.

For Rachel Pappas, “just breathe” does not apply to her when she runs on the soccer field.

Pappas, a women’s soccer player at Eastern, cannot simply come off the field and take some deep breaths and be ready to go again right away.

When she runs on the field, she suddenly cannot breathe.

In fact, breathing has nothing to do with how she recovers from getting winded, rather a Botox shot in to her vocal cords is the only solution she knows of that helps her be able to play more.

Pappas played soccer all her life and continued that passion at Eastern.

Now a senior, in every season, she had to come out of the matches sometimes after just a couple minutes because she literally cannot breathe, something that frustrates her a lot.

Pappas would have to sub out of the match and take a couple minutes to catch her breath on the sideline because “waiting it out” is all she can do.

The most obvious causation for her symptoms would be asthma.

“I don’t actually have asthma, and I thought I did up until a couple years ago,” she said. “So I’ve been taking inhalers my entire life, pretty much, since I think like middle school. And nothing worked, so it was frustrating and then I got to college, and I was still trying, like, multiple breathing treatments.”

At that point, a couple sources told her what may actually be causing her trouble: Vocal Cord Dysfunction (VCD).

You probably have never heard of it because, according to the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, asthma and VCD have very similar symptoms, like difficulty breathing and coughing.

The difference, though, is that a person who has asthma experiences their airways tighten; someone who has VCD experiences their vocal cord muscles tighten.

“It’s kind of a really rare, random thing,” she said with a laugh.

One of the sources who tipped Pappas off that she may have VCD was a doctor she visited once she was at Eastern, whom Pappas added was one of many doctors she visited.

The other source was a complete stranger.

“My mom actually found this girl on Facebook that had (VCD) and she got Botox,” Pappas said. “My mom messaged this girl and that was how we figured it out.”

The girl told Pappas how the Botox treatment worked, which is how Pappas started thinking about getting the treatment herself.

The girl herself thought she had asthma before being diagnosed with VCD, and she wrote about it on Facebook, which is how Pappas’ mom found the girl: The perfect person for Pappas to talk to.

In her freshman year at Eastern, Pappas said she still used inhalers and the breathing treatments she was instructed to do: Neither helped.

Then, in her sophomore year, the Botox started.

“The first time I got it, it was really bad I was freaking out,” she said. “I’m not good with needles, it was terrible, but now every time I get it it’s gotten easier. It’s not fun, but I can do it.”

Getting the Botox treatment is somewhat a bother in itself: Pappas said the person applying the Botox numbs her throat and has to find her vocal cords, which requires Pappas to say “ahhh” and the person applying it to find the cords based off the sound waves.

On top of that, she goes to Rush University in Chicago to get the treatments, so she has to travel approximately six hours round-trip for it.

Pappas said the treatment usually works, though sometimes, it leaves her voice raspy for awhile.

Despite this, the treatment works… most times.

Before each soccer season the last few years, Pappas got the Botox treatment, but before this season, it did not work.

During the preseason, she was upset it did not work, and in the first couple matches, she could not play that many minutes.

Karina Delgado | The Daily Eastern News

Rachel Pappas has a rare disorder called Vocal Cord Dysfunction, which means that her vocal cord muscles tighten up when she runs, making it hard to breathe.

Around three weeks ago, she had to go back for a second treatment, which ended up working.

“It’s been hard because, ever since last year maybe sophomore year, I’ve had a starting spot that I haven’t been able to really fill, which sucks,” Pappas said. “Then the only way I can get that is if the Botox works, so it is frustrating because I have all these high hopes, then I get (the Botox) then it doesn’t work and I have to play a different role on the team.

She continued: “At first it was really hard because it’s like a big mental challenge, I’m frustrated so frustrated that I can’t play but I know I have to just overcome it and do what I can for the team because I don’t want to be selfish.”

Although the Botox worked, Pappas said she is not sure how long it will last because it is different every time.

“I’m enjoying it while it lasts, but I have really no expectations of when it’s going to stop (working),” she said.

The Botox treatment paralyzes her vocal cords to stay relaxed so they do not tighten and cause the lack of air.

But when the VCD does kick in, the only way to stop it is to stop running and take a short rest.

This creates a dilemma for Pappas because, as athletes know, there are certain ways to breath when exercising.

Balancing the normal breathing that comes with exercising with the treatment Pappas received is something she herself has not figured out.

“Yeah, see, I couldn’t do that,” she said. “When they first diagnosed me with VCD, they were giving me speech therapy and they would teach me how to breathe again, even just sitting here, which is fine. But then I’m like, ‘How am I supposed to do that when I’m running and trying to pass a ball?’ For me, it was impossible to try and do that.”

Since the Botox takes care of the breathing aspect, Pappas said she can then completely focus on playing.

The interesting part is that the VCD only kicks in when she is running; more specifically, when she makes a change in pace or when she runs up-and-down bleachers or stairs.

“So, basically the rest of my life I’ll just have to monitor it and I can’t really do sprints,” she said.

Otherwise, in her average day when she is not running, everything is fine.

When the VCD does kick in, though, she compared that feeling to crying.

“When you’re about to cry, it always happens to me, my throat closes, and that’s kind of what happens to me when I can’t breathe,” Pappas said. “I just feel like there’s nothing coming in.”

Without the Botox, Pappas said she can only play 5-to-10 minutes at a time due to the running.

The big struggle with VCD never made her think about quitting, but at the beginning of this season, when the Botox did not work, Pappas said her mom asked her why she would stay on the team if it was not working because she knows her daughter gets frustrated with the VCD.

“I told her, ‘I know you probably won’t understand this, it is extremely frustrating, but to me the team means a lot and I know when I go to practices I still contribute,’ and mentally I know what I’m doing, I can help the other players get to where they need to be,” she said. “So I would never quit, it’s definitely at times very frustrating and I have to take a second and calm down, but no I would never quit because I do love soccer and the few minutes that I do play for me are worth it.”

Pappas’ teammates support her, and the women’s soccer team’s head coach, Jake Plant, told her he will play her as long as she wants to play.

As for Pappas’ future with VCD, she is not completely sure what will happen. She knows for sure, though, that she will not be able to run or sprint without feeling the effects of it.

“Usually people grow out of this rather than grow in to it, and I’m growing in to it so my doctor’s kind of confused,” she said. “For me, I’m growing in to it and it’s getting worse so I don’t know, I hope it’s not going to get worse.”

Pappas said the first time she encountered breathing difficulties was seventh or eighth grade, and the problem will seemingly persist throughout her life, when she sprints at least.

In middle school, she said she could play a whole half with no problems, but the VCD got worse to the point where she can only play a couple minutes without needing a break.

But, despite the troubles VCD presented to Pappas, she has found those rare moments where she could play all 90 minutes of a match.

Most recently, she played a whole match after getting that second treatment of Botox a few weeks ago.

“(Against Chicago State Sept. 15) I played 90 minutes, which is awesome, so I’m doing pretty good right now,” she said with a smile and upbeat tone. “My first 90-minute game was last preseason when I got it, and it was against Ball State I remember, and I was so excited because I played 90 minutes and I felt so good.”

Dillan Schorfheide can be reached at 581-2812 or dtschorfheide@eiu.edu.