Column: Our generation is not the dumbest one

January 12, 2017

One of my professors asked me to read a selection from Mark Bauerlein’s hit social commentary The Dumbest Generation as winter pre-reading for a class. I tried to swallow my pride while I read it, but it can be hard to remain neutral when you go into an experience already implicitly insulted. Dumbest Generation, you say? What a perfect way to get young people to read your book. Nevertheless, I tried my hardest to give Bauerlein the benefit of the doubt.

Very quickly I had to drop the selection. I was only asked to read the introduction and the first chapter, and I could not even bring myself to do that. Normally I do not take notes while I read nonfiction unless I intend to use the information for research, but I filled an Evernote screen with ravings and rebuttals. I was downright incensed.

For those who are not familiar with The Dumbest Generation, I shall swallow my pride for a moment to provide you a summary. The Dumbest Generation is a hand-wringing account of how the Information Age dulled the edges of what should have been the smartest, best equipped generation in history: namely, Millennials. The author bemoans how young people cannot recite basic factoids once considered the basis of a decent recall memory, how we refuse to attend to the fine arts even though performances and galleries are far more available today and how, by all measures, we waste our time with new media and pop culture consumption.

I cannot refute the author’s introductory points, to be perfectly honest. In fact, I agree with him on the base facts: yes, we do not recall basic facts as easily as our parents, and no, we do not tend to go to operas and ballets.

However, I take issue with the author’s insistence that the changing tide of culture and the changing bases of knowledge and value are indicative of a weaker generation. At the surface level it does seem that our refusal to attend to the traditional bastions of culture and intelligence is just stupidity, but when you begin to pick at the edges, the arguments unravel into something more ugly.

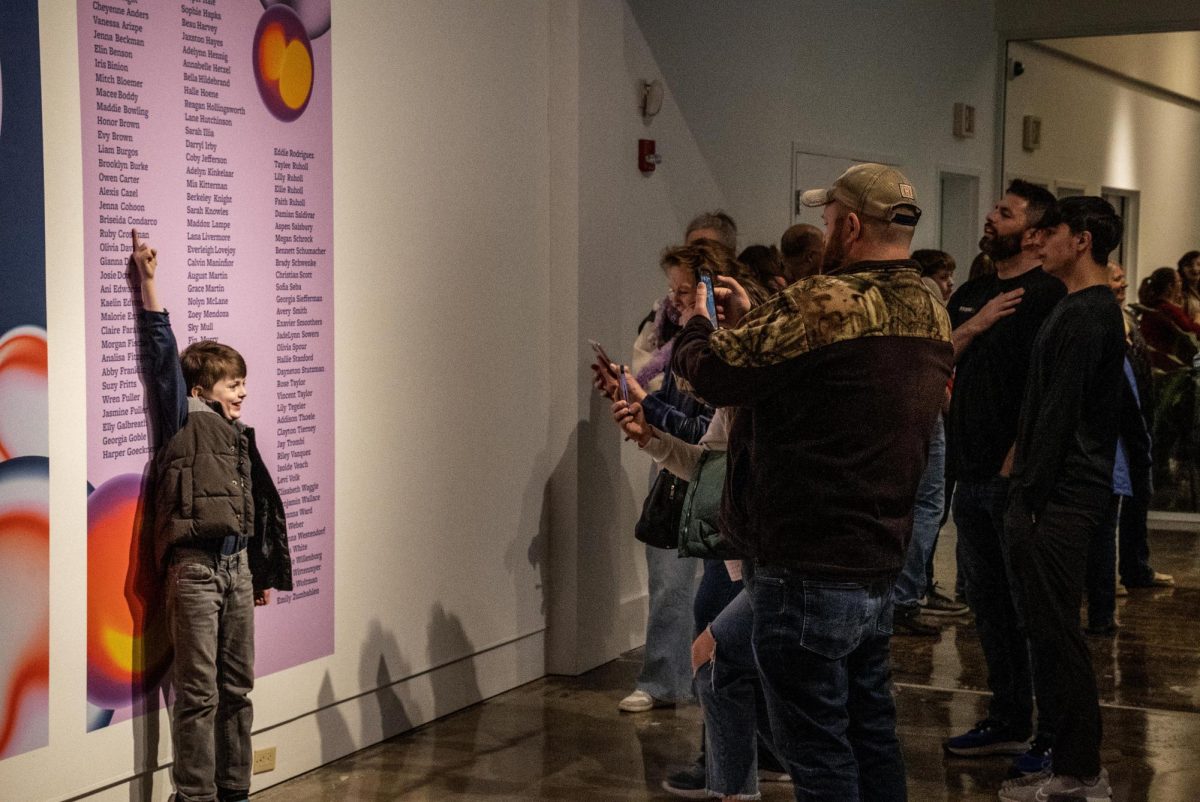

For the sake of time I will only focus on one of Bauerlein’s complaints. The first I would like to address is his argument that young people do not appreciate the fine arts because we show up for plays, operas, concerts, galleries and recitals in fairly low numbers.

My generation, granted, does not value operas like my parents’ generation did. But my generation is also an entirely different beast.

My generation is more diverse than any other generation. People in my peer group come from cultures the world round, from little-appreciated cultures here at home and from cultures that might have been stigmatized before. Sure, we skipped out on the opera when it came to town, but was opera an important cultural and musical experience for all of us?

Maybe my generation stayed away from the opera because their religion forbids instrumental music. Maybe we stayed away because we wanted to spend some time at the drag show instead, learning about the history of queer people who paved the way for us. Maybe we preferred to go see Kendrick Lamar that night instead, and maybe we have a pretty solid argument for why his music is just as high of an art.

In fact, maybe we stayed home because we were working on our own songs. Maybe, too, we avoided the gallery because we chose to create our own art.

When you judge a generation by its adherence to the values of previous generations, you do not necessarily end up with a picture of a generation that values its traditions and is therefore intelligent or vice versa. Instead, you end up with a picture of how similar or different a generation is to the ones before it. Our generation, obviously, is wildly different from those before us. Of course our values are different.

Furthermore, using traditional measures of culture and value betrays a bias towards the old guard of worth. Who is to say that opera is intrinsically more valuable than any other form of music? Is our valuation of opera entirely based upon its musical merit, or is it blended into a system of value that always prefers more European forms of expression or in more male forms of expression?

My generation is not stupid for avoiding the Old Boys’ Club of artistic and intellectual merit. If I go see a ballet and my friend watches a step show on Youtube and her friend attends a drag ball, we have all learned and become better people for seeing something new, no matter what the experience was.

Why should the most diverse generation in American history act like the old generations, anyway? If anything, we should be celebrating our newness.

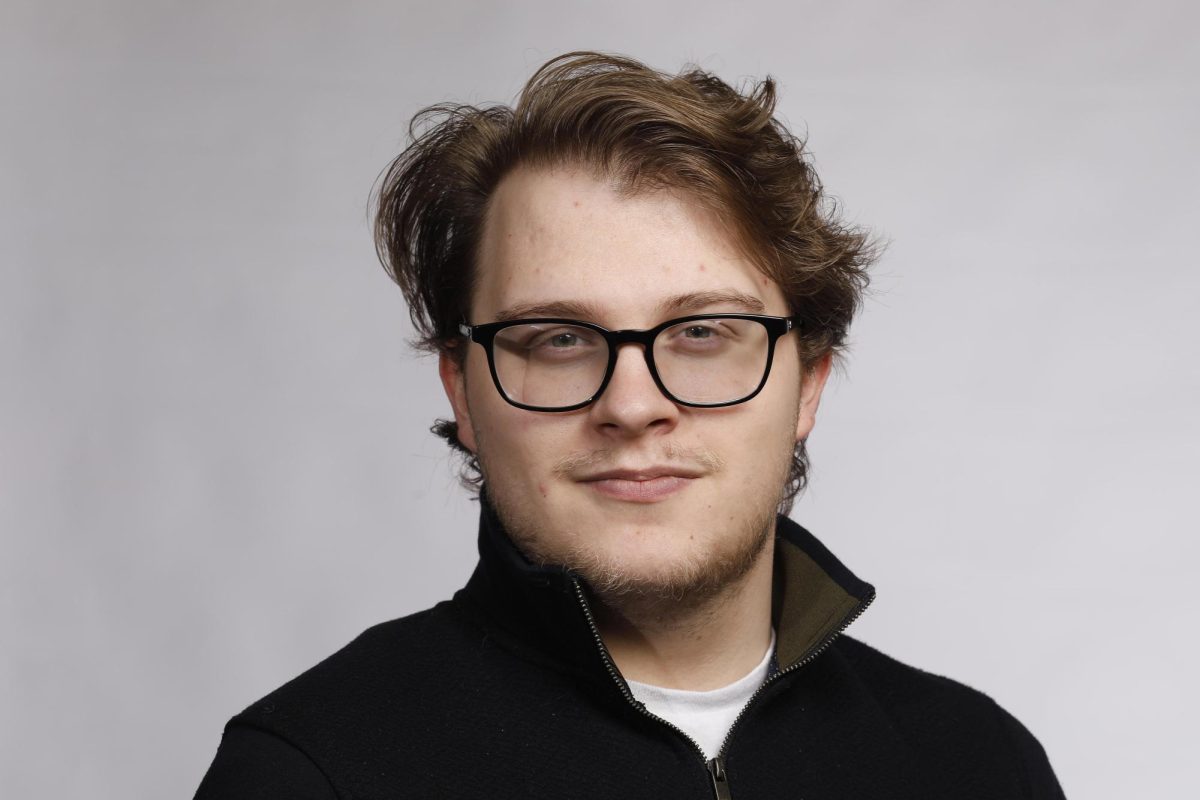

Shelby Niehaus is a senior English language arts major. She can be reached at 581-2812 or scniehaus@eiu.edu.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Junior right-handed Pitcher Lukas Touma catches at the game against Bradley University Tuesday](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MBSN_14_O-e1743293284377-1200x670.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)

![The Weeklings lead guitarist John Merjave [Left] and guitarist Bob Burger [Right] perform "I Am the Walrus" at The Weeklings Beatles Bash concert in the Dvorak Concert Hall on Saturday.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WL_01_O-1200x900.jpg)

![The team listens as its captain Patience Cox [Number 25] lectures to them about what's appropriate to talk about through practice during "The Wolves" on Thursday, March 6, in the Black Box Theatre in the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WolvesPre-12-1200x800.jpg)