Editor’s Note: This column has been updated with a correction as of 2/2/16.

The urge to give is a great thing. Many people give frequently when presented the opportunity, whether they give generously or not. However, not many people actually research charities before placing money in their hands. This can be unwise, depending on the charities one interacts with.

To avoid giving money to unscrupulous or inefficient charities, it’s important to evaluate every charity thoroughly. The best way to evaluate a charity is to check their financial records, usually on Charity Navigator. According to Charity Navigator, the best charities use at least 90 percent of their funds on program expenses. For example, the Susan G. Komen Foundation uses just under 50 percent of its revenue for education and around 26 percent of its revenue on breast cancer screening and treatment, ranking it as less than efficient.

Not every piece of information about a charity is available on Charity Navigator, however. Some charities function on misinformation, even when their ratings may technically be good. Take for instance Invisible Children, the charity that created the infamous Kony 2012 campaign and its viral awareness scheme. While it holds a three- of four-star rating on Charity Navigator (a star more than the Susan G. Komen Foundation), this charity functions on misleading and dangerous false information.

As the Huffington Post claims, tensions in Uganda are a long-standing, deep-rooted affair, and removing a single man from the scheme will not fix the problem at its origin. Furthermore, another Huffington Post reporter claims that Joseph Kony has not been sighted since 2010.

Furthermore, even if a charity is technically airtight and well intended, the charity’s moral code and functions may be unsavory for some people. For example, while the Salvation Army does good work, they discriminate against LGBT people, and I no longer donate money to them through personal preference.

There are some other red flags that some charities send up that are less obvious than the first few. While these red flags are telling, they may not be a sign of corruption or disorder when seen individually. They are simply smaller evaluative tools.

One of the red flags is a “free stuff” model. Remember Invisible Children? Their charity model, when cultivating the Kony 2012 campaign, involved sending loads of free knickknacks to their donors. Sturdy wristbands, bags, glossy posters and advertising materials, t-shirts… all for a quaint little donation price. After all that manufacture, however, where has that donation money gone?

Another red flag is the disease commodification used by so many medical charities. Disease commodification is when a major illness is turned into a selling point, often to the point of divorce from any significant interaction with charity. Many breast cancer charities are guilty of this tactic, but again, the Susan G. Komen Foundation is the most obvious, largest target.

Some charities also use manipulative tactics to get donations or give services. For instance, according to a 2014 NBC News article, PETA, in interacting with Detroit, Mich. residents during their ongoing water crisis, paid the water bills of 10 families who pledged to try a vegan diet for 30 days. Of course, this sounds chintzy and possibly harmless, but in reality, it’s a means of making the needy jump through hoops to receive something a charitable organization already posessed and was willing to give. It also does not take into account the expenses that go into vegan diets, and Detroit’s vast food desert (in which healthy foods are hard or impossible to come by).

The Buy One, Get One model, while slightly less sinister, is also a red flag for some charities. Toms has been criticized for using this model to send canvas shoes overseas to impoverished Africans. It’s a nice idea, but most impoverished people abroad need jobs, training, and infrastructure rather than items. Also, overseas donation models tend to weaken existing business in struggling economies.

Finally, beware charities that promise mission trips to connect with children. These are the most benevolent-seeming– one could travel abroad and make a real difference in a child’s life! Dig a little deeper, though, and it becomes obvious that many other people have been given the same offer to change a child’s life. This child has seen friends walk in and out of their life, ripping new holes in their trust every few weeks.

Before giving to a charity, check them out on Charity Navigator, and look for their financial data. If at all possible, give locally, and give items that the charity has said they need. Alternatively, one may also give directly to research labs, shelters, and hospitals rather than navigate a third party.

Charity is a great thing, and very praiseworthy most of the time, but beware: don’t part with money that won’t be going to a just cause!

Shelby Niehaus is a junior English and English language arts major. She can be reached at 581-2812 or scniehaus@eiu.edu.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Charleston High School sophomore Railyn Cox pitches the ball during Charleston's 8-7 win over Flora High School on Monday, March 31.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/SBHS_01_O-1-e1743982413843-1200x1023.jpg)

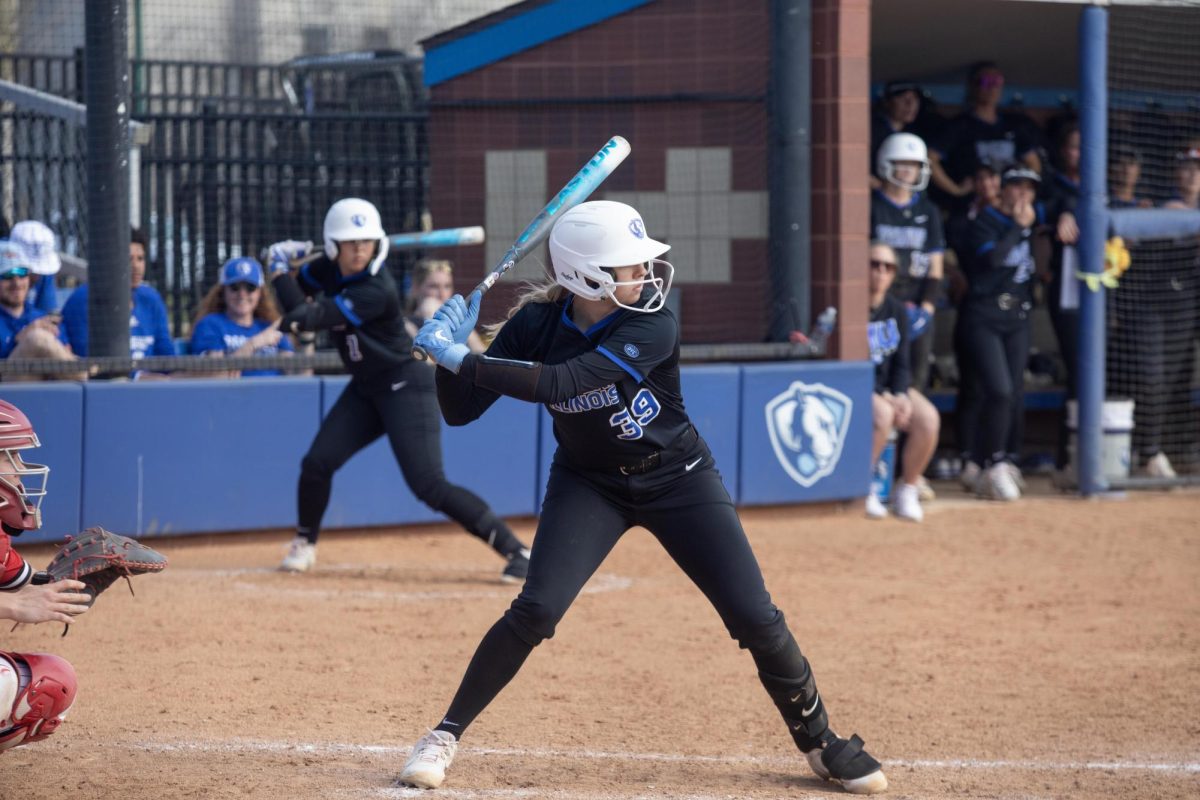

![[Thumbnail Edition] Eastern Illinois softball senior infielder Briana Gonzalez resetting in the batter's box after a pitch at Williams Field during Eastern’s first game against Southeast Missouri State as Eastern split the games as Eastern lost the first game 3-0 and won the second 8-5 on March 28.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/SBSEMO_11_O-1-e1743993806746-1200x692.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Junior right-handed Pitcher Lukas Touma catches at the game against Bradley University Tuesday](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MBSN_14_O-e1743293284377-1200x670.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)

![The Weeklings lead guitarist John Merjave [Left] and guitarist Bob Burger [Right] perform "I Am the Walrus" at The Weeklings Beatles Bash concert in the Dvorak Concert Hall on Saturday.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WL_01_O-1200x900.jpg)

![The team listens as its captain Patience Cox [Number 25] lectures to them about what's appropriate to talk about through practice during "The Wolves" on Thursday, March 6, in the Black Box Theatre in the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WolvesPre-12-1200x800.jpg)