Breaking the silence

Austin Parrish sat in the living room of his home in Pendleton, Ind., across from his mother, Cindy, who had no idea what her son was about to admit.

“I need to tell you something, but I don’t know how you’ll react” Austin said to his mother. “I just need to know that you’re going to be there for me and love me no matter what.”

Cindy assured Austin that she would love him no matter what.

“That’s when I began to choke up and I wasn’t able to talk,” Parrish said.

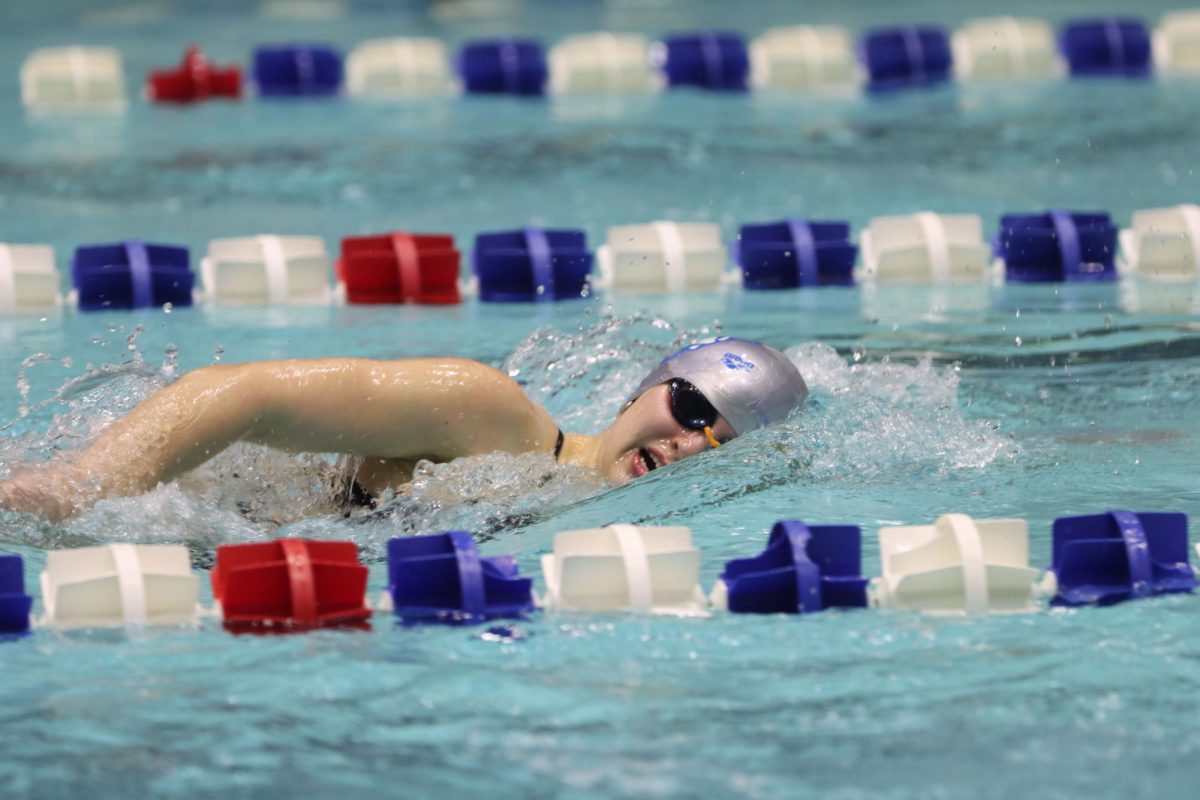

Finally, on a Tuesday in April 2011, a 16-year-old Austin, now a freshman on Eastern’s swim team, was able to muster up the strength to declare what he had been contemplating since he was in fourth grade.

“I’m not attracted to girls,” Austin said to his mother. “I’m attracted to the same sex. I find guys to be more attractive than girls.”

Austin came out as gay.

Cindy sat silently for several seconds — for what seemed like an eternity to her son — before she fled the living room in tears and bolted upstairs to her bedroom.

She locked the door. Austin sat alone.

His mother came from a strict religious background. For that reason, to this day, Cindy’s side of the family is unaware that he is gay. Therefore, he foresaw such a reaction from her, but nonetheless he was not prepared for the magnitude of witnessing it in person.

“Seeing her cry upset me,” he said. “I felt like I let her down; I can no longer make her proud.”

For 10 minutes Austin sat alone in his living room. His mother finally came back downstairs where she began to ask a series of “general” questions: Why do you think this? Are you sure? How do you know?

“Just the typical questions asked when a person comes out,” Austin said. “I told her what it was, ‘girls, I just see them as friends. I don’t see myself being married to one or having a relationship with one. That’s simply just that.’”

Silence flooded the room once again. Parrish apologized to his mother for upsetting her.

“She didn’t really say anything,” Austin said. “She kind of just got up and left.”

Lack of interaction continued between Austin and his mother for the next month. Austin said he would go to school at Pendleton Heights High School, go to swim practice, come home and go straight to his room.

Austin shut out everybody. Dinners were silent. The silence was drowning his life.

“It was that awkward feeling, that elephant in the room,” Austin said. “It’s there, but nobody addressed it.”

Nobody addressed Austin being gay because his father, Bill, still did not know. His younger brother, Tyler, had caught on. He told his two older sisters, Christina and Katie, two days before he told his mother.

Each of his siblings accepted the reality, Austin said. For his mother it was not so easy. And for his father, Austin knew he would have a similar, if not worse, reaction.

So Austin put off the unbearable task of coming out to his father.

“Every so often my mom would tell me, ‘you need to tell your dad,’” Austin said. “I would just say, ‘I can’t. I just can’t do that.’”

Growing up, Austin’s father, Bill, was the stricter parent and was seen as the authoritative figure in the family.

“I knew what made him tick and what would upset him,” Austin said.

Austin said he knew that telling his father he was gay would undoubtedly upset his father, so he elected not to do so.

Austin refused to tell his father. His mother refused to keep it from him any longer, so she eventually told him. Austin was not present when his father found out.

Bill addressed Austin about being gay a couple days later and told his son that he might simply be confused. But Austin knew he was not.

“These are my feelings,’ Austin said. “I can’t change them.”

Still, Austin’s parents asked him to see a therapist, to which he refused at first. Eventually, Austin’s parents convinced him that seeing a therapist was best for them to understand how he felt.

Austin said it was pretty much he went to one session or his parents would not accept him being gay.

Austin was willing, under the impression that he would be the only person in therapist’s office. However, since he was not a legal adult, his mother had to accompany him.

Austin was forced to answer questions that he did not want to have either of his parents hear at the time: Why he thought men were more attractive? Did he think his mother would never talk to him again?

“After seeing her initial reaction, I was scared she would disown me and want nothing to do with me,” Austin said he told the therapist.

Again, Cindy burst into tears.

“‘You’re my own flesh and blood,’” Austin said his mother told him. “‘I can’t just throw you aside. You’re the same person you were yesterday; you’re just not living a lie anymore.’”

Still, Austin was not comfortable with talking to the therapist. He did the one session his parents asked, and he was done. He threatened his parents if he had to go again, he would move to live with a friend or one of his sisters.

“They never made me go again,” Austin said.

His parents grew more accepting of Austin being gay. But a year and a half later, his father was diagnosed with Viral Herpes Simplistic Encephalitis, the virus that causes cold sores to flare up.

For Bill, however, the virus entered his blood stream and infected his brain, causing his frontal tissue to swell up and put pressure on his frontal lobes.

Bill suffered short-term memory loss — forgetting the number of kids he had, let alone that his oldest son was gay.

Austin said Bill also lost a large portion of his motor skills. The once outgoing, conversational father he had, whom Austin took after, was now quiet and reserved.

“There’s maybe 10-20 words exchanged between us when I go home,” Austin said.

This time, Austin made the decision to again not tell his father that he was gay. Bill eventually caught on, but actually confronted his son about it, Austin said.

“It wasn’t as difficult the second time because he never fully understood it,” Austin said. “He tries to not acknowledge it now. He pushes it aside.”

As for his mother, Austin said the two are closer now than they have ever been before. The two talk every day, as he makes it a point to send a text or make a phone call back home.

At the last meet of Panthers’ 2014 season at Eastern, the Summit League Championships on Feb. 19 in Indianapolis, Ind., Cindy was there to see her son.

Austin’s mother watched from the bleachers, as he achieved career highs in the 200-yard breaststroke, 400-yard individual medley and the mile freestyle.

“She is going to support me, no matter what, in everything I do,” Austin said. “It means so much to know that she still cares.”

Anthony Catezone can be reached at 581-2812 or ajcatezone@eiu.edu.