What the Egyptian revolt should teach us

There are countless lessons to take away from the revolt that has consumed Egypt and captivated the world. For example, if police brutality is a major grievance in your country, making National Police Day an official holiday is probably going to cause some problems down the road.

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak might wonder, in his coming years in exile, whether the protests could have been avoided if he had instead declared Jan. 25 National Free Dinner and a Back Rub Day.

Here in the U.S., the Egyptian revolt is another reminder about why it sucks to be the world’s lone superpower.

Here is a brief, and inadequate summary of events as of Sunday evening: On Jan. 25, protests were organized against the authoritarian government of Mubarak. The recent revolution in Tunisia, another Arab nation in North Africa, helped give the protests enough momentum to tap into 30 years of disappointment, resentment and anger toward Mubarak and his government.

Soon, protests of tens of thousands grew to riots of hundreds of thousands. With the world media watching, Mubarak shut down access to Internet and cell phone reception, sent riot police out in full force and set up a curfew. Hardly anyone paid attention to the curfew and riot police soon fled the cities. Instead of stepping down, Mubarak announced his appointment of a vice president (read: successor), and the army was sent out to the streets to maintain some semblance of order.

As it stands, the army, who enjoy a great deal of public support and were cheered upon entering the city, have not fired on the protesters. There has been looting, though not as much as one might expect from a city the size of New York without any police presence. Over 100 people have died. Protesters say they will not stop until Mubarak is gone.

Statements from President Obama and Sec. of State Hillary Clinton have changed in tone over the last few days. Initially, they called for nonviolence on both sides and for Mubarak to have a dialog with the protesters about instituting real democratic reforms. As the protests grew, and it became clearer that Mubarak is likely to be ousted as president, Obama and Clinton said the U.S. supports the basic human rights of free expression and self-government. And on Sunday, Clinton laid the groundwork for Mubarak’s departure, calling for, “an orderly transition to meet the democratic and economic needs of the (Egyptian) people.”

This kind of weak-kneed support for whoever is on top at the moment can be infuriating to hear from the people who represent America. After all, these are a people who are trying to throw off the shackles of an authoritarian regime that denies them the democratic means to achieve the basic rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. If America doesn’t stand for that, what does it stand for?

Sadly, it’s not as simple as that. The U.S. has supported the Mubarak regime, politically and militarily, for decades. Depending on your point of view, the reasons for that are probably either more or less cynical than you imagine.

Egypt is at the center of the Arab world-geographically, economically and politically. The relationship between the U.S. and Egypt is crucial for progress in Arab-Israeli peace talks. The Suez Canal, controlled by Egypt and open to the U.S., is a vital strategic point for our military to protect interests in the region.

America has supported the Mubarak regime because it has provided stability in a country that, in many ways, leads the Arab world, and there is a good argument to be made that such support saved many lives, if not the nation of Israel. But that has also meant supporting a regime that denies basic rights to its people.

It is impossible to predict the outcome of an Egyptian revolution. It could usher in a democratic, secular, modern Egypt that could bring the rest of the Arab world into the 21st century. It could be an adversarial Islamic regime similar to Iran, or it could resemble a more moderate, forward-leaning country like Turkey.

Perhaps the greatest lessons to be learned from the current turmoil in Egypt is that the West needs to reject the false choice between authoritarian stability and Islamic extremism. Time will tell.

For now, it is the Egyptians who must free themselves from the Pharaoh. The Red Sea is theirs to part.

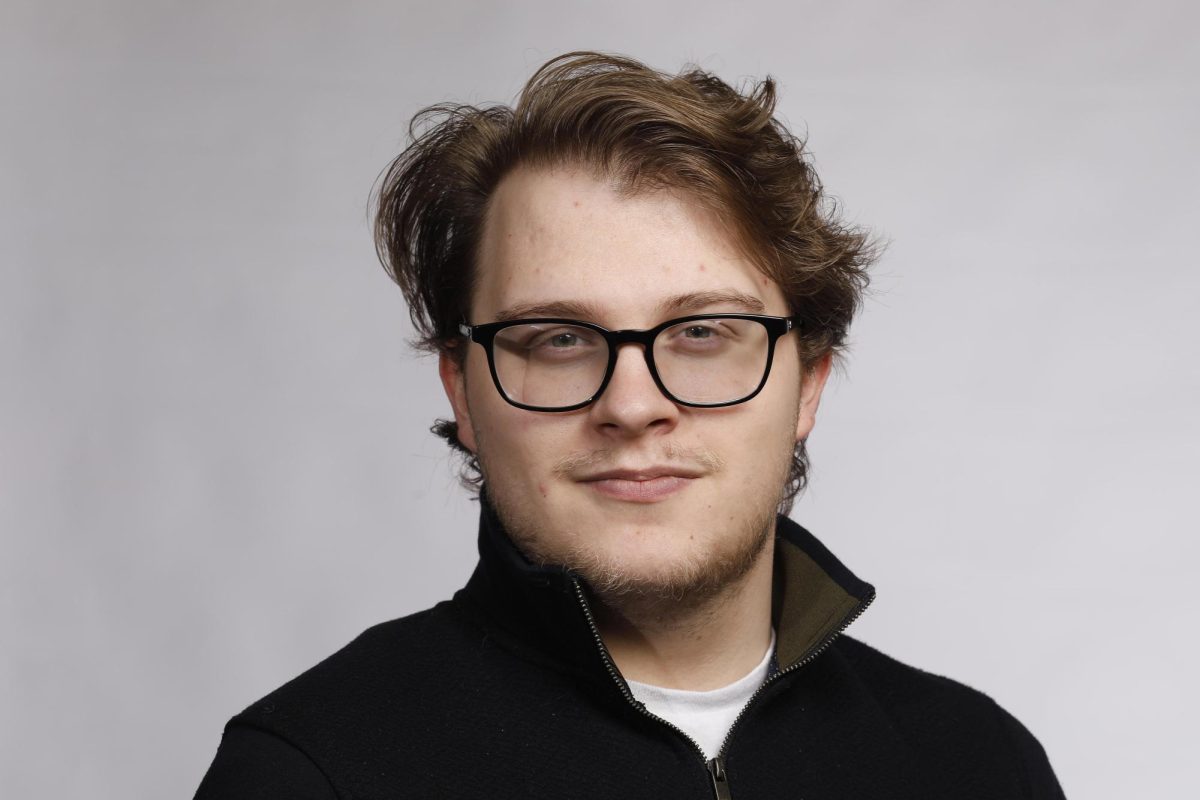

Dave Balson is a junior journalism major. He can be reached at 581-7942 or

DENopinions@gmail.com.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Junior right-handed Pitcher Lukas Touma catches at the game against Bradley University Tuesday](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MBSN_14_O-e1743293284377-1200x670.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior Foward Macy McGlone, getsw the ball and gets the point during the first half of the game aginst Western Illinois University,, Eastern Illinois University Lost to Western Illinois University Thursday March 6 20205, 78-75 EIU lost making it the end of their season](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_OVC_03_O-1-e1743361637111-1200x614.jpg)

![The Weeklings lead guitarist John Merjave [Left] and guitarist Bob Burger [Right] perform "I Am the Walrus" at The Weeklings Beatles Bash concert in the Dvorak Concert Hall on Saturday.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WL_01_O-1200x900.jpg)

![The team listens as its captain Patience Cox [Number 25] lectures to them about what's appropriate to talk about through practice during "The Wolves" on Thursday, March 6, in the Black Box Theatre in the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WolvesPre-12-1200x800.jpg)