Professor examines femicide in Mexico

Neyrac Cervantes was 15 years old when she disappeared. She was not a prostitute or addicted to drugs, but poor. She worked at a men’s clothing story. Every night, she would walk home. But one night in 2003, she never came home.

Hundreds of pink, wooden crosses line the highways in Juarez and Chihuahua, Mexico. Each one represents a young woman, like Cervantes, who has either been murdered or reported missing.

Juarez is a sister city to El Paso, Texas, and Chihuahua City is in Chihuahua, the largest state in Mexico.

In the past ten years, more than 400 women have been murdered in these two towns and another 600 reported missing.

Angela Aguayo, communication studies professor, has seen the crosses, talked to the families of the missing women, and made a documentary – along with Alex Hivoltze-Jimenez, a graduate student at Boston University – to tell Cervantes’ along with the other missing women’s stories.

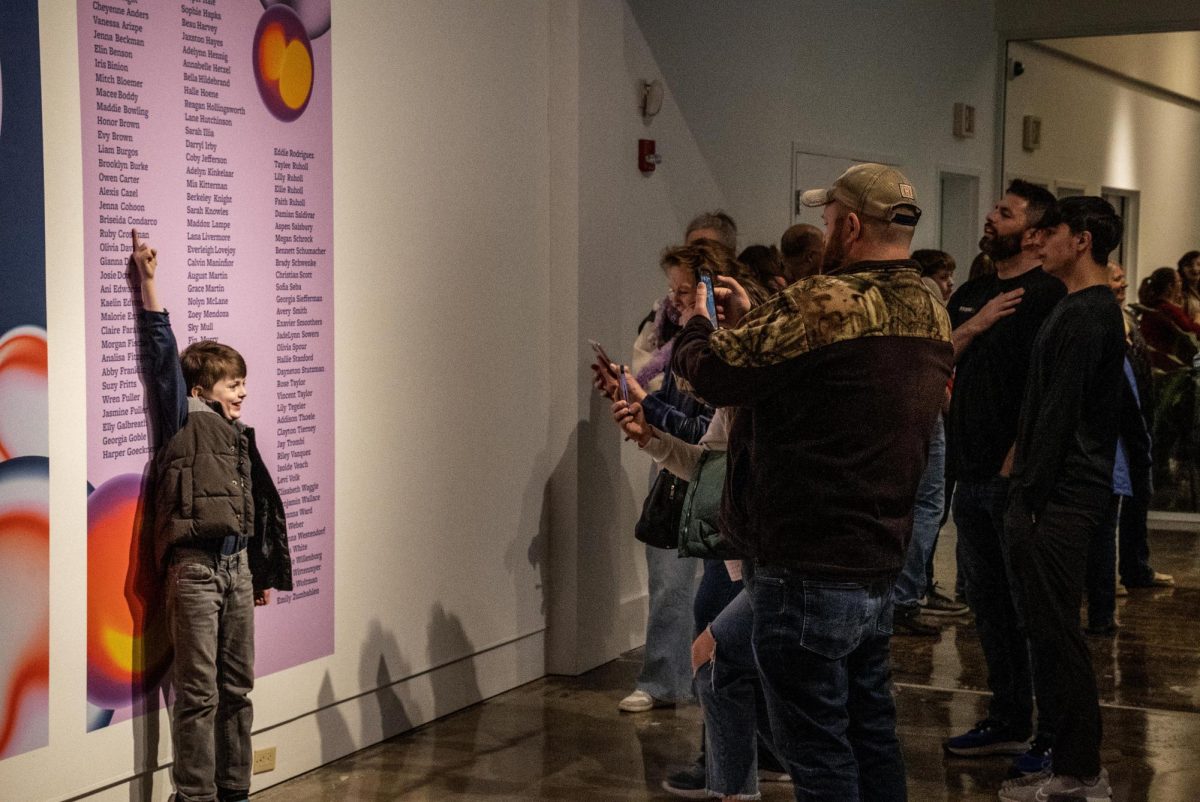

Aguayo and Hivoltze-Jimenez debuted their documentary titled, “Ni Una Mas” last night in the Charleston/Mattoon Room in the Martin Luther King Jr. University Union as part of Eastern’s Latino Heritage Month Celebration.

“There’s a serious problem – in terms of a culture – in it being okay to murder women,” Aguayo said to introduce the film.

For the most part the local authorities do nothing, said Macrina Cardenas, legislative coordinator for the Mexico Colidarity Network, in the film while standing alongside a highway where several pink crosses stand in gravel dirt. The network coordinates tours where people can learn more about the situation in the two cities. Cardenas was Aguayo and Hivoltze-Jimenez’s leader while they filmed their documentary.

Aguayo is planning a second trip to Juarez with in the next year. Students, professors and staff interested in getting involved can email her at ajaguagyo@eiu.edu.

Afterward showing the film, the two and Suzanne Enck-Wanzer, communication studies professor, lead a discussion about the disappearances, the Mexican media coverage, the failures of the local governments to solve the murders and what students can do to get involved.

Enck-Wanzer, whose research focuses on domestic violence, brought the women’s deaths to a more local level.

What happens when we start talking about femicide as our problem, she asked attendees. She gave an example of an estranged wife. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 1,500 women are killed in the United States each year by their spouses.

How do you prevent rape on campus, was another question she asked. Audience members replied, “Don’t walk alone at night,” or “Don’t wear short skirts.” She then asked, “What do you tell men?” The room was silent. Exactly, she responded.

Get men to stop seeing abusing women as their cultural right and the violence will stop, she said.

Hivoltze-Jimenez echoed this idea when he talked about intersections or the point when two things meet and looking at the point. For example, the intersection of day and night: When does day become night, he explained after the presentation.

“Intersection for me, these killings are being judged by the sacred and the profane,” he explained while illustrating an intersection of religion and gender.

If a woman is defined as a profane thing, then violence is acceptable, he said.

“We are all living a nightmare that will never end,” Neyrac’s mother said in Spanish on the film about the problems her family has experienced with the law and media coverage since her daughter’s disappearance.

The local authorities produced a body and said it was Neyrac’s. The family sent the body’s DNA to the United States for outside confirmation. When the results returned – after the Cervantes family has buried the remains – the test determined that the body did not belong to Neyrac.

The authorities also accused Neyrac’s father and cousin with her murder; both were tortured, Aguayo said. Her father was later released, but the cousin was jailed for three years and only just released two weeks ago.

The family does not believe the father and cousin committed the crimes. Nor do they believe she died because she was a prostitute or drug addict, a characterization made by the local newspaper and authorities of the women who disappear.

Tears come to her eyes while Neyrac’s mother tells the camera: “My daughter is a young woman like you.”

She holds a picture of her daughter with the word, “justicia” written across the top.

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior tennis player Luisa Renovales Salazar hits the tennis ball with her racket at the Darling Courts at the Eastern Illinois University campus in Charleston, ILL.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Tennis_01_O-1-e1741807434552-1200x670.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior right-handed pitcher Tyler Conklin pitching in the Eastern Illinois University baseball team's intrasquad scrimmage at O'Brien Field in Charleston, Illinois on Jan. 31.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/TC_01_O-e1741567955534-1200x669.jpg)

![[Thumbnail Edition] Senior, forward Macy McGlone finds an open teammate to pass the ball too during the game against the Tennessee State Tigers 69-49, in Groniger Arena on the Eastern Illinois University campus, Charleston Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WBB_02_O-1-e1741228987440-1200x692.jpg)

![E[Thumbnail Edition] Eastern Illinois softball freshman utility player Abbi Hatton deciding to throw the softball to home plate in a fielding drill during softball practice at the field house in Groniger arena on Tuesday Feb. 11.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/SB_03_O-e1741208880750-1-e1741209739187-1200x815.jpg)

![The Weeklings lead guitarist John Merjave [Left] and guitarist Bob Burger [Right] perform "I Am the Walrus" at The Weeklings Beatles Bash concert in the Dvorak Concert Hall on Saturday.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WL_01_O-1200x900.jpg)

![The team listens as its captain Patience Cox [Number 25] lectures to them about what's appropriate to talk about through practice during "The Wolves" on Thursday, March 6, in the Black Box Theatre in the Doudna Fine Arts Center in Charleston, Ill.](https://www.dailyeasternnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/WolvesPre-12-1200x800.jpg)